Introduction

Palatal expansion in adult patients is a relatively new concept. Ever since “Grays Anatomy” the “bible” for dental students studying anatomy, we all believed that the cranial sutures fuse solid when we become “non-growing adults”. In an interview for Dental Press Magazine of Orthodontic and Facial Orthopedics in 2002, Donald H Enlow, author of three books on Cranium Facial Growth and 170 scientific articles, Dr Enlow, when queried “Is there any craniofacial growth after 20 years of age?” Answered,“yes”. Futhermore, he states, “ A capacity for facial remodeling in adults is retained throughout life”. He also states,“We must utilize three-dimensional evaluation based on an individual’s actual growth and development.” The Homeoblock™ functional appliance produces noticeable facial changes in adult patients in four to six months. We have viewed these changes in three-dimensions using “stereophotogrammetry”. In an article published “Quantification of facial morphology using stereophotogrammetry–demonstration of a new concept.” It is concluded that “ stereophotogrammetry is a suitable 3-D registration method for quantifying and detecting developmental changes in facial morphology.” (1)

Abstract

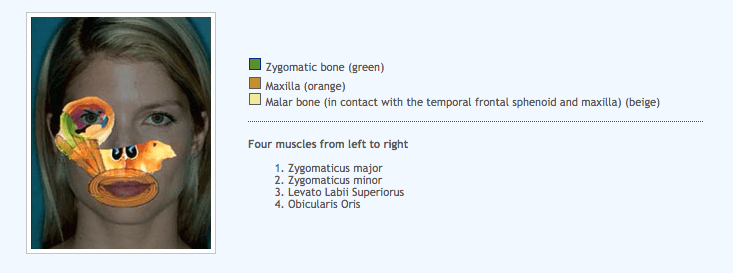

Maxillary arch changes using the Homeoblock™ appliance have been reported and published in the Functional Orthodontist (2). The purpose of this paper is to look more closely at the facial changes that occur when we remodel the maxillary dental arch wider in the course of palatal expansion. To observe and understand these changes a review of the anatomy of the region is included.

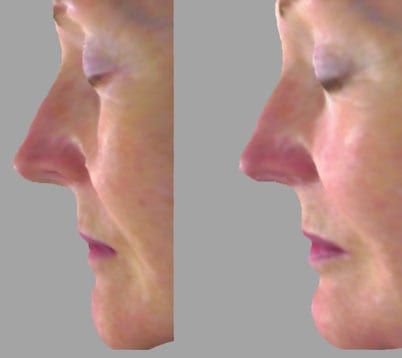

Looking at the anatomy of the area we can see how the remodeling of the maxilla can easily affect the malar and the zygomatic bones. Since the muscle attachments are on the bone we can see how the muscles which insert into the muscle and soft tissue around the mouth can also affect the fullness of the lips. Optimal development of the lateral aspects of the face especially the malar and zygomatic bones make it easier for the patient to smile. The paper will examine three dimensional images of patients, pre and post treatment with the Homeoblock™ appliance. We choose the profile view to illustrate the changes most clearly. It is concluded that the Homeoblock™ appliance creates observable changes around the eyes, in the area of the cheekbone and around the mouth.

Case Reports

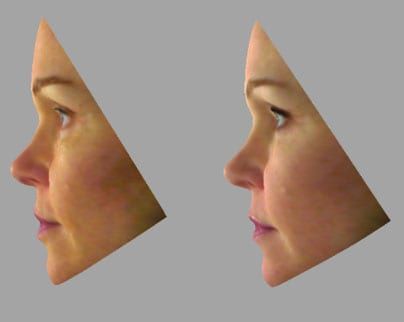

Patient A

The first patient is a sixty year old female that presented to the office for teeth straightening, and porcelain laminate veneers. A three-dimensional Stereophotogrammetry image was taken using a 3dMD facial capture system.

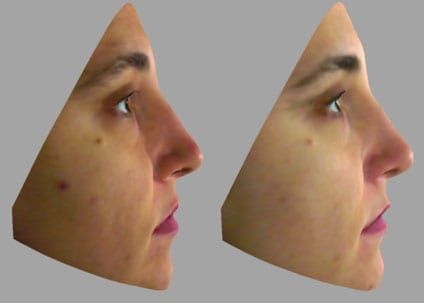

Patient B

The second patient a fifty year old female was treated six months with a Homeoblock™ appliance to reduce age lines in the face. Stereophotogrammetry images were taken pre and post treatment. The photos were then evaluated using the 3dMD facial capture software to evaluate the changes that occurred.

Patient C

The third patient is a thirty-six year old female that presented to the office for teeth straightening with the Homeoblock™ appliance. She was treated for thirty months wearing the appliance in the night time only to straighten her upper and lower teeth.

Discussion

The issue of facial esthetics and functional orthodontics is very timely. There is a growing focus on esthetics, which needs to be balanced with good functional outcomes. The Homeoblock™ appliance has several components in combination, including a base-plate with a unilateral bite block and a mid-line expansion screw. We postulate that the unilateral bite block exerts cyclic, intermittent forces on the periodontium of the associated teeth during function (such as swallowing during sleep). These forces are detected by mechanoreceptors on the cell surfaces of the periodontal and periosteal cells. Due to signal transduction(3), a cascade of events is initiated, resulting in gene transcription and mRNA biosynthesis(4). Downstream, osteogenic cells are activated, and adapting to the axial forces, remodeling occurs. The change in vertical dimension (opening the bite) affects also the spatial relations of the contra-lateral teeth(5), which have lost their normal occlusal contacts. These changes are also detected by receptors in their periodontal and periosteal cells. Consequently, remodeling occurs due to signal transduction, adapting to decreased forces in accord with the functional matrix hypothesis(6-7).

The Homeoblock™ appliance has also a base-plate that does not contact the palatal vault. Consequently, swallowing of saliva creates a relative negative pressure between the palatal mucosa and the fitting surface of the device. As the dorsal surface of the tongue exerts forces on the polished surface of the device during swallowing, tension is exerted on the mucoperiosteum of the hard palate and the midpalatal suture is separated. Thus, the developmental mechanisms of sutural homeostasis are activated(8). Despite the fact that most osteogenic activity is normally observed during early to late childhood, it is now understood that palatal, maxillary and circum-maxillary sutures retain biosynthetic potential into late adulthood (9), and it is possible that mechanical stimuli up-regulate genes that are not typically expressed during normal development(10). It is postulated that the Homeoblock™ device maintains physiologic forces on the midpalatal suture, resulting in slow expansion (250µm per week). Recent research suggests that a sutural width >300µm results in bone deposition(11) while a sutural width <300µm is thought to arrest bone deposition and/or initiate bone resorption. Thus, Homeoblock-induced mechanotransduction may result in remodeling activities that affect facial morphology. The net results of this protocol are thought to evoke the maxillo-mandibular spatial patterning that is encoded for at the level of the genome.

According to the functional matrix hypothesis(12), the mandible and mandibular dentition form a spatial matrix(13) that is responsive to the maxillary complex. The unilateral bite-block of the Homeoblock™ appliance activates the lateral pterygoid muscles that displace the mandible anteriorly and inferiorly, providing space for putative condylar remodeling. Therefore, it is conceivable that during the correction of palato-maxillary structures the Homeoblock™ appliance will produce spontaneous correction of the mandible(14) due to neuromuscular activity. Simultaneously, the base-plate of the Homeoblock™ appliance displaces the tongue anteriorly and inferiorly, so that it contacts the lower anterior teeth intermittently. These neuromuscular responses may aid in relieving lower incisor crowding in conjunction with the mandibular expansion screw, while the flap springs aid in the correction of the spatial alignment of the mandibular dentition. Therefore, the ultimate result of the Homeoblock™ device is thought to evoke enhanced symmetrical dentofacial development(15-18) that is genetically encoded for each individual.

References

1. Ras F, Habets LL, van Ginkel FC, Prahl-Andersen B. Quantification of facial morphology using stereophotogrammetry–demonstration of a new concept. J Dent. 1996 Sep;24(5):369-74.

2. Singh GD, Diaz J, Busquets-Vaello C, Belfor TR. Soft tissue facial changes following treatment with a removable orthodontic appliance in adults. Funct Orthod. 2004;21(3):18-23.3. Sandy JR. Signal transduction. Br J Orthod 1998; 25:269-274.

4. Mao JJ, Nah HD. Growth and development: hereditary and mechanical modulations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;125:676-689.

5. Iscan HN, Sarisoy L. Comparison of the effects of passive posterior bite-blocks with different construction bites on the craniofacial and dentoalveolar structures. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:171-178.

6. Moss ML. The functional matrix hypothesis revisited: The role of mechanotransduction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:8-11.

7. Singh GD. On Growth and Treatment: the Spatial Matrix hypothesis. In: McNamara JA Jr (ed). Growth and treatment. Craniofacial Growth Series. Monograph 41. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2004.

8. Mao JJ, Wang X, Mooney MP, Kopher RA, Nudera JA. Strain induced osteogenesis of the craniofacial suture upon controlled delivery of low-frequency cyclic forces. Front Biosci 2003;8:A10-17.

9. Kokich VC. The biology of sutures. In: MM Cohen Jr (ed). Craniosynostosis: Diagnosis, evaluation and management. New York: Raven Press, 1986.

10. Mao JJ, Nah HD. Growth and development: hereditary and mechanical modulations. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2004;125:676-689.

11. Borke JL, Yu JC, Isales CM, Wagle N, Do NN, Chen JR, Bollag RJ. Tension-induced reduction in connexin 43 expression in cranial sutures is linked to transcriptional regulation by TBX2. Ann Plast Surg 2003;51:499-504.

12. Moss ML. The functional matrix hypothesis revisited: The role of mechanotransduction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1997;112:8-11.

13. Singh GD. On Growth and Treatment: the Spatial Matrix hypothesis. In: McNamara JA Jr (ed). Growth and treatment. Craniofacial Growth Series. Monograph 41. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2004.

14. Lima AC. Spontaneous mandibular arch response following rapid palatal expansion: a long term study on Class I malocclusion. MS thesis, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2004.

15. Belfor TR, Singh GD. Developing facial symmetry using an intra-oral device. J Cosmetic Dent 2004;20:76-80.

16 Belfor TR, Singh GD. Developing dental arch symmetry using the Homeoblock device. Int J Orthod 2004;15(3), 27-30.

17. Singh GD, Diaz J, Busquets-Vaello C, Belfor TR. Soft tissue facial changes following treatment with a removable orthodontic appliance in adults. Funct Orthod. 2004;21(3):18-23.

18. Belfor TR, Singh GD. Treating malocclusions and improving orofacial form and function in adults. J Amer Acad Gnathol Orthop 2005;22(1), 14-17.